“Previously built architecture is a maintenance issue more than anything else.” – Gordon Matta-Clark1

Maintenance plays a crucial role in the production of architecture, yet by and large architects have treated it with indifference. Despite its existence everywhere, the history of maintenance has been neglected as part of the discourse from within architecture.2 Dismissed as irrelevant to form making and design, maintenance has been cast aside, appearing (if at all) in the back-section advertisements of architecture magazines or categorized as a problem to be undertaken after construction, not treated as a disciplinary concern or as having any relevance to the production of an art form.3 Perhaps this is because buildings deteriorate slowly and imperceptibly, but this disciplinary disaffection is undeserved. With the day-to-day wear and tear on surfaces, buildings eventually decay if left unkept. Labor is required through the form of maintenance to keep buildings looking new. But maintenance is more than labor; it is a result of work performed by architects in their making of buildings. Following the philosopher Hannah Arendt’s distinction between labor and work, looking at maintenance offers a new representation on work or a “lasting thing.”4 And now more than ever it is time to pay attention to it, as our contemporary architecture culture values images of those things that are new or appear to be new rather than lived in, and privileges a work of art in its original form. Understanding the complexities required for an image to endure is not abstract, and not about labor alone. While architecture has turned a blind eye to the subject of maintenance, others have made it the object of their work, primarily through art, revealing new realities and subjectivities that architecture should revisit.

By making maintenance the subject of their work, artists reveal that, in the postmodern split between art and life, maintenance was cast on the side of life and technology – within architecture, especially, forgotten and removed from primary imagery, and when it

was introduced, rendered as a technical act performed without consequences for the creative act of design. Yet maintenance is needed if beauty is to endure. It is labor. But it can be argued that it both produces work and affects the production of work. This portrayal of maintenance emphasizes its routine qualities and the endless repetition of skilled labor it requires. Maintenance, unlike general cleaning, should not be categorized as part of what Arendt called “reproductive” labor – manual acts of unskilled labor.5 Maintenance should be understood as labor, but skilled labor, especially when it involves large-scale buildings like towers. Meanwhile, buildings require labor and work if they are to be considered imageworthy, a goal in which maintenance plays an inherent part. In modernism, architects thought through the problem of maintenance as part of the architecture, and the division between art and life did not yet exist. It is time to rethink the relevance of maintenance’s effects on contemporary architectural practice, image production, representation, and culture at large.

Artists, on the contrary, have continued to challenge our notions of endurance and permanence in response to modernism and neo-avantgarde approaches toward art and work. As early as the 1960s and 1970s, people like Mierle Laderman Ukeles and Gordon Matta-Clark brought issues of maintenance and spectacle to the fore in projects like, respectively, “Manifesto for Maintenance Art” (1969) and Conical Intersect (1975). This book examines a range of art practices-historical and contemporary – in order to address the problem of maintenance from an architectural perspective, and speculates how expanded thinking on the subject could impact future design and discourse. When a careful look is taken at the intersection between art, architecture, and maintenance, the recursive problems of subjects and objects surface in interesting ways.

Maintenance originates as a modern concern, though unlike cleaning, its more domestic counterpart, it is not a “happening,” as in the kinds of spontaneous events the artist Allan Kaprow created. But contemporary artists have recast it as a “happening” through their works, repositioning the subject as “cool.” While maintenance is not the origin of architecture, in architecture it is possible to find an origin of maintenance. Thinking back to projects such as Buckminster Fuller’s Dymaxion House (1929) or SOM’s Lever House (1952), it is clear that issues of upkeep at both the domestic and urban scales were coming to the fore by the mid-twentieth century. Maintenance as a subject aligns itself with philosopher Martin Heidegger’s reading of Dasein‘s experiences regarding tools, things of nature, and other human beings as being-in-the-world.6 Through a careful reading of archival building photographs and architectural drawings, maintenance’s history can be found.

Not until the early twentieth century did photography become a widely accepted mode of architectural representation in magazines, newspapers, books, and elsewhere. Photographs became the way to circulate images of buildings to wide audiences, while simultaneously bringing problems of iconography and imageability to the discipline. Maintenance is a subject that appears and reappears throughout modern and contemporary histories of architecture, but also in contemporary art. It is impossible to do without maintenance unless the desired outcome is decay or death. Through images of maintenance, both in architecture and in art, it is possible to see the various roles that it plays.

This book is primarily concerned with a few specific types of buildings – the private house, pavilions, and high-rise buildings – and, because of the significance of images in the modern period, it pays particular attention to buildings constructed with novel and developing materials, technologies, and precise detailing. This includes modern buildings like Lever House (1952) and the U.S. Steel Building (1971), and contemporary buildings like the Beijing Water Cube (2008) and the Netherlands Embassy in Berlin (2004). The architects Alison and Peter Smithson present an imperative to assess this kind of work in their “Prelude” to The Heroic Period of Modern Architecture:

One further thought. No one has properly observed a quite definite special sub-category of modern architecture. An architecture of the enjoyment of luxury materials, of the well-made, of the high finish. It is special to Mies and occasional to Le Corbusier and Gropius.7

Taking the Smithsons’ prompt, Maintenance Architecture examines buildings in this special subcategory, citing a range of modern and contemporary works that take on maintenance as a subject without “one-thingly character.”8 Maintenance is deeply connected to issues of imageability and architecture’s present-day concerns. It is more than a problem of trying to be or appear eternally new. Maintenance presents evidence of nature, evidence of human relationships beyond the technical.9

The evolution of building construction methods, in conjunction with the increasing prevalence of architectural photography, began to produce a kind of architecture that based its worth on spectacle and iconicity over a lived experience. Today we cannot separate this kind of performance from other things. The significant things are those that are “close to us,” as Heidegger once said about airplanes and radio sets; the things that are close to us through technology, ultimately, are about the essence of an epoch, but simultaneously also bring us close to one another, physically or through information.10 For modern architecture, the photographs that captured the buildings in a certain state – that of newness or appearing new – kept the discipline close. But further following this thought, and looking more inward, maintenance is really the thing that brings us close and keeps us close. Its effect of continual newness contributed to a new representation: the photograph.

While the repetition of carefully selected images printed in black and white perpetuated the mythos of modern architecture, the expression of architecture through multiple media and modes of representation is necessary for contemporary projects. Ezra Stoller, the famous photographer whose photographs captured the modern moment, literally rendering the time period, was part of a bygone age; the fixed and singular image is no longer the only thing available, because of the proliferation of media today. These images no longer stand alone, but are instead viewed in the context of other images propped up against other forms of media from videos to blogs, Flickr streams, Instagram feeds, and so on. Architecture that bases its worth on the creation of iconicity and spectacle assumes it will endure in part because it is captured and archived online, instantly and forever available. Recently, the rapid and unprecedented growth primarily in the Middle East and Asia has likewise produced an image culture that is varied yet abundant. While it may be unrealistic to think of limiting a building through a singular or select set of discrete image(s), the way that an image or set of images endures has new meaning in today’s endless yet fleeting image culture; this is especially true for buildings that are public and urban.

The recent diversity of architectural works, styles, and ideologies has produced a crisis in the assessment of work and images. Without unifying evaluation criteria across the discipline, we have returned to a focus on performance, examining architecture through the lens of its built life. This is by no means a new concern – we need only remember the American oil crisis of the 1970s, the creation of Paper Architecture, and the beginnings of postmodernism to pull the discipline away from performance into “real architecture.” The focus on issues around technology and sustainability is reemerging as a way to think about architecture, but it only exacerbates the split between life and art. This way of thinking is an extension from the late 1990s and early 2000s building boom where realism became subsumed across the disciplines of architecture and art. In many ways architecture during this period leaned heavily on advances in allied fields like structural and climate engineering. Architecture could be advanced only by enveloping other disciplines, and in this moment those particular disciplines were largely based in technology.

Maintenance carries the expression of architecture’s essence and represents it as a forward-thinking practice (or not). If maintenance can formulate a line of questioning in the Heideggerian sense of a “question builds a way” and “the way is one of thinking”11 – then through maintenance it is possible to see a dialectical relationship with architecture. For instance, the Seattle Public Library, one of the most celebrated buildings of the early twenty-first century, advances the discipline through its form and function, and also through technology. But does it advance beyond its technological bounds? The building is cleaned by the most basic and dangerous method: a cleaner on a rope. The use of the squeegee here creates an unmediated relationship between humans and the architecture – bringing the building closer to problems of handicraft. This is a strange way to read a building, with its advanced diagrid facade that collapses structure and enclosure into one system. There is a glamour of the uncelebratory overlaid onto the celebratory, but perhaps there was no other way to solve the problem of cleaning, and the theatrical stunts of the window washer set against the backdrop of the building add to the recursive story of the building, even if it is absurd. We may never know.

Within contemporary architectural discourse, maintenance remains insufficiently defined, except in specialized and technical contexts. Rarely thought of in social or design terms, maintenance has been more readily explored and experimented with in allied disciplines like preservation, material science, development, policy, insurance laws, and building codes. Even as new forms of practice and built work begin to question the limits of its more standard interpretations, the concept of maintenance has not evolved much in recent years.

Furthermore, an important distinction should be made between cleaning and maintenance. The two are frequently misinterpreted: often maintenance is interpreted as cleaning. But cleaning is more generally associated with domestic, and therefore private and individual, activities: dusting, polishing, or vacuuming. Maintenance instead requires formal organization and teams of skilled workers, operating in public. Where cleaning engages the discrete parts of a building, maintenance is dedicated to safeguarding the holistic image of an architectural work. Each has a unique temporal quality as well. Cleaning is concerned with a building’s use at a particular moment; maintenance represents an investment in the persistence of architecture – both as an image and as an ideal.

Maintenance will become increasingly important as architects adopt practices that are to affect environmental performance and also the making of environments.12 In modernism, architects presented the building cycle with falsely constrained endpoints – conception and realization – that hinged on the parallel production of idealized images.

These pivotal points have cultivated a narrow understanding of architectural reality, often omitting the life of the building and its performance. An expanded building cycle that incorporates maintenance has the potential to affect the future of architecture by contributing to the cycle of creation, building, occupancy, the representation of architecture, and image circulation, which in turn will impact future invention.

Contemporary artists have pursued the subject of maintenance perhaps more than architects, for whom it is really the most pressing. The artists discussed in this book are often active participants in their work, performing cleaning tasks almost always staged within celebrated works of architecture. Artists choreograph scenes that disrupt iconic images of architecture in order to reveal the tasks of cleaning. In some cases – as with Job Koelewijn’s Cleaning the Rietveld Pavilion (1992) or Iñigo Manglano-Ovalle’s Le Baiser/The Kiss (1999) – there is a kind of overperformance for effect, where the artists implement tools and dress associated with a kind of industrial cleaning in excess of both their task and the architecture being cleaned. In so doing they call into question something more than just cleaning. Their works deal with the representation of architecture and with labor that is robust, organized, social, and temporal.

Art practices also reveal technology, and have specifically illuminated the relationship between architecture and the maintenance workers who bring buildings to the forefront of our consciousness through their repetitive labor. Here we can turn to the window washer who exerts forceful energy across a building’s face. There is a particular beauty in the striking contrast of the image of the maintenance worker floating in front of a glass curtain wall. The scale of the body against an unrelenting grid has a diminishing effect on the body, but the beauty of the architecture is also disrupted by the image of the worker, reminding one that architecture is not complete. Maintenance in all its clumsy, barebones mechanics is an act of renewal or rebirth, even though it has primarily been thought of as a technical act of repair. In Morning Cleaning, for example, Jeff Wall broaches two paradoxical aspects, the everyday and the modern, by staging the event of cleaning. And while the everyday reenacted here is neither flat nor deadpan, it constructs a world that is never revealed.13

In architecture culture, maintenance can be understood through two concepts that have been circulating of late: performance and post-occupancy. Post-occupancy is a relatively new term that has been adopted into architectural discourse as a means of reconciling the recent and all-too-consuming movement toward realism. Coined to describe the period after a building has been completed, when it has begun to be inhabited, the term places importance on the life of a building rather than on the ideas surrounding its form making. Post-occupancy plays off the professional definition of occupancy, which describes the number of building users and the building’s occupancy type, such as assembly, office, residential, and so on.

Unlike building or design codes, post-occupancy offers calculable elements of knowledge – information or data such as natural elements from temperature to rainfall, or performance-based criteria such as specifications that can be used for evaluation and feedback. It is important to note, however, that these terms should be understood beyond the purely technological – they cannot be separated out from the social or cultural. In a period of tremendous production of the real, it makes sense that there would also be an abundant effort to absorb built work and its effect on discourse. It remains to be seen whether post-occupancy can create a new paradigm for evaluating architecture or effectively support the existing significance attached to form making. Post-occupancy seems to emerge on the side of the owner, the user, the inhabitant, or the specialist, and less so of the design architect, and so there is the danger of it only further fragmenting the discipline. Where post-occupancy takes root is up for grabs; but if it is rethought, it can be a place for new ideas and will deeply affect allied practices in addition to architecture itself.

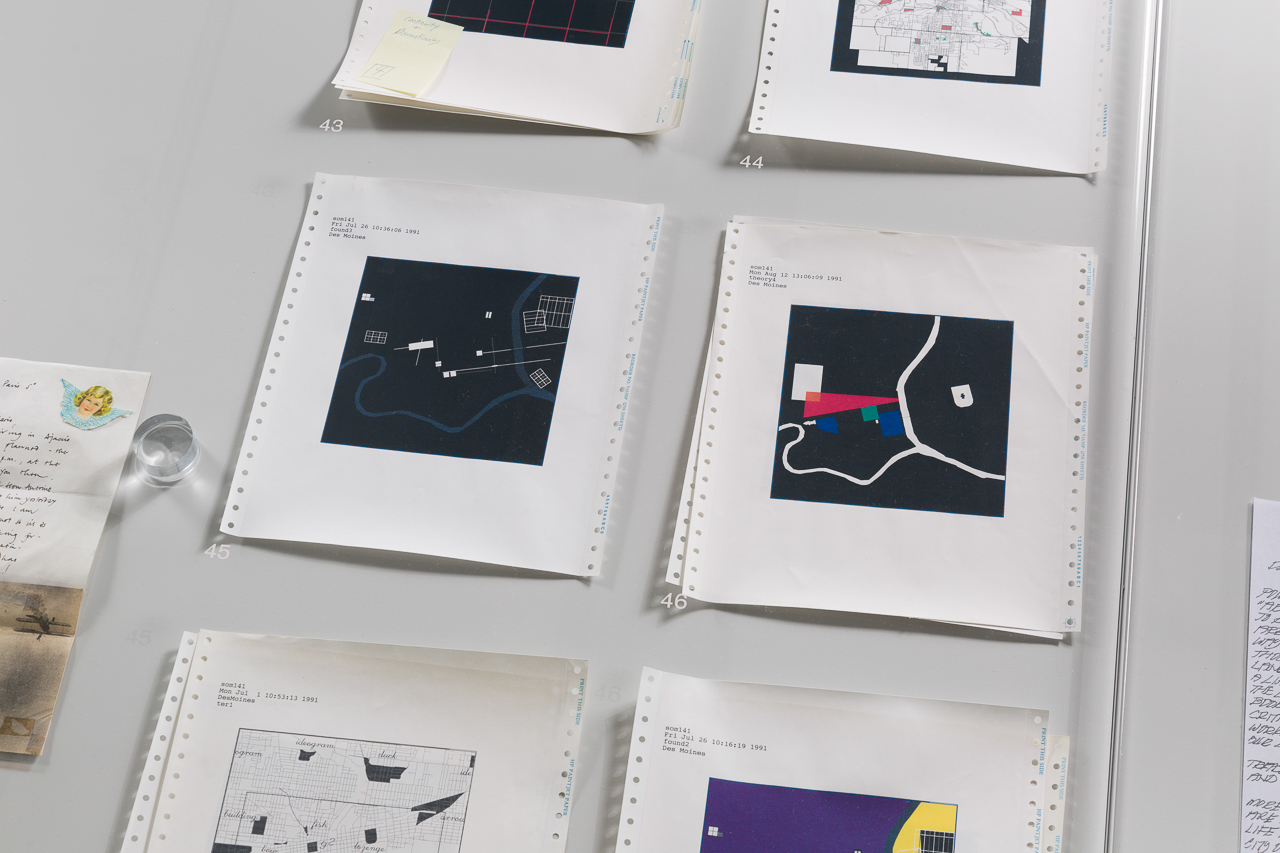

Interest in preservation and in post-occupancy has come to the forefront over the last two decades, in parallel to the building boom or in spite of it. Most recently, these two subjects were explored through two architecture venues, one an exhibition and the other a book. At the 2010 Venice Biennale, director Kazuyo Sejima of SANAA asked exhibitors to consider the interaction between architecture and its occupants under the title “People meet in architecture.” In presenting an entirely new body of work on this topic, the Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas with OMA/AMO curated the exhibition Cronocaos, arguing that their work had always been concerned with time and history: “OMA and AMO have been obsessed, from the beginning, with the past.”14 This exhibition presented a select group of materials that became an archive of “fragments” of the total collection of buildings in a range of mediums, from photographs to a series of graphic posters with quotes, charts, and statistics on the subject of preservation; “project cards” made to look like postcards could be torn off a wall and taken with the viewer. The cards featured projects from OMA, including the Maison à Bordeaux, the overscaled fluorescent orange bean bag from the Maison à Bordeaux that was part of another exhibition, Content, and oversized photo albums. The posters were used as a place to locate specific quotes on theories about architecture’s endurance from critical figures like Ruskin and Viollet-le-Duc. On one exhibition poster, featuring an image of Ruskin and Viollet-le-Duc alongside each other, Ruskin is saying: “Do not let us deceive ourselves in this important matter; it is impossible, as impossible as to raise the dead, to restore anything that has ever been great or beautiful in architecture”; while Viollet-le-Duc declares: “To restore a building is not to repair it, nor to do maintenance, nor to rebuild it, it is to reestablish it in an ultimate state that never existed before.” The exhibition announced: “The interval between the now and the preserved is shrinking, and is about to disappear. From this moment, we do not only have to look back, but also forward; we will have to decide what to preserve in advance.”15 This statement underscores the compression of time between a building’s completion and its canonization. To designate a work of architecture a “historic monument” amplifies the burden of care, and raises questions not only around restoration or preservation but also those critical to creative making. Furthermore, deciding “what to preserve in advance” means reclaiming an aspect of the discipline that has been parceled out to specialists and historians. It urges architects to address preservation before a project is realized, and this includes the subject of maintenance, which is new territory in that it has not yet been theorized and the consequences are unknown. And while maintenance may seem like a separate act, not part of the discipline or discourse of architecture, I would argue that there are subtle shifts and slight visual adjustments that are made as a result of maintenance. As buildings go from daily maintenance to large-scale interventions such as labor done for preservation or restoration, I would still argue that all three things effectively change their appearance. Maintenance performed on a building before it becomes a monument is fundamentally different from when it is performed afterward. Inevitably, there will be codes, practices, and strategies to be put in place when we are trying to uphold a new yet re-created image of the building. If “preservation is overtaking us,” maintenance was there first.16 Preservation is in a way a singular act; maintenance is ongoing. In philosophy, endurance is questioned through a series of acts in looking: for instance, if something passes between an object and a viewer, is it still the same object? If the answer is no, if that object is indeed something other than the original, then this logic could be extended to acts performed on buildings, such as maintenance. In this way, it can be argued that even though the act of maintenance may not leave a trace, it fundamentally changes the image of a building, the image of its architecture. This may not seem particularly significant, but it can open up a new way of thinking whereby architecture is not fixed once a building is complete. Architecture is almost never new and, even more important, its aim should not be to remain new, singular, or fixed. In Post-Occupancy (a “special issue” of Domus, entrusted to an editor-architect of worldwide renown who illustrates architecture according to his own original codes of communication), Koolhaas presents four projects: the Netherlands Embassy in Berlin, Seattle Central Library, McCormick-Tribune Campus Center at IIT, and Casa da Música. These works, he writes, “represent the realities we were complicit in creating, post-occupancy, as facts, not feats.”17 But these facts are still feats, particularly when they come up against the subject of time.

Maintenance is a reaction to and a momentary covering up of time’s terror.18 Manglano-Ovalle is captured through upclose stills from his film Le Baiser/The Kiss, dressed in his orange janitor suit, intently cleaning the glass façade of Mies van der Rohe’s Farnsworth House. His pleasure in cleaning is intimately portrayed, perhaps as an attempt to return the house to a place that has been refreshed and reflects the original – “an action for a certain sense of responsibility” – and to avoid “empirical mediocrity.”19

Maintenance occupies a particular space and moment in the life of a building. It comes after design, after construction drawings – those documents that record the future realities of the project – but exists after building, between acts of building and preservation, and again after preservation or restoration. It would be, in a way, what Jacques Derrida speaks of as “operating in silence, it never leaves any archive of its own.”20 It is only through art that maintenance gets recorded and archived, even if those records are fake, staged fictions. If architecture has had a disciplinary amnesia about maintenance, it was the art world that created “the possibility of memorization of repetition, of reproduction, or of reimpression.” And to further this, Derrida goes on to say, “we also must remember that repetition itself, the logic of repetition, indeed the repetition compulsion, remains, according to Freud, indissociable from the death drive. And thus from destruction.”21 Architecture and architects have typically been figures of completion: completing the model, the design, the details, the job site inspection. Maintenance somewhat undoes this completion, requiring us (architects) to be vulnerable and in need of community.22 If, as Karsten Harries suggests, “What weighs on us is not so much that we are powerless, but that we repress that powerlessness and the associated emotions . . . hard to accept our temporality,”23 and “The historical dimensions of our environment must be preserved and represented if we are to keep open the possibility of genuine dwelling. And we do not preserve or represent history by just playing with its fragments,”24 I would then argue that sometimes it is only by looking through fragments that a clearer picture of what has occurred can be revealed. Maintenance offers a way of looking at the world, and artists who incorporate maintenance in their work are, in effect, re-presenting architecture back to us.

Each generation draws its own parameters around the discipline: sometimes the role of the architect stops at the idea, sometimes at the drawing, and sometimes at the built work. Each building process requires a unique approach, depending on which aspect the owner, architect, or society prioritizes above all the others: the concept or intent, the construction documents, the physical building, or its reproducible image. It remains to be seen whether architects will choose to stay involved in the constructed lives of their designs, and whether that involvement is even desirable. But one thing that seems to continually be at the core of architecture is its representation.

“Post-occupancy” offers a way to see what happens in the absence of the author; as Koolhaas suggests, maintenance is one component of post-occupancy. Its representation calls into question the very nature of architecture, since the imagery of maintenance, at first blush seeming only technical, would have nothing to do with beauty.25 The performative aspects of architecture remain repressed; instead, architecture constructs value through idealized representation in publications. Reflecting on architecture in The Heroic Period of Modern Architecture (1995), the Smithsons write that the purpose of their book was an exercise in gathering images that meant the most to them personally. This collection, when put together and ordered, made – in their words a “work-document” that presented photographs and drawings of buildings which constituted a “harmonious whole.” The book’s mission was to focus on the way modern architecture had been represented through images of completed buildings. The series of black-and-white images collected enabled them to offer a synopsis of the period: “this is probably the last collection of its kind. The next collection in forty years’ time of the architecture of our own period will be quite different for it will not record buildings,’ but built-places, and the documents will be mostly air views, sequential photographs, and system explanations.”26 They conclude (as quoted above): “No one has properly observed a quite definite special sub-category of modern architecture. An architecture of the enjoyment of luxury materials, of the well-made, of the high finish. It is special to Mies and occasional to Le Corbusier and Gropius.” In the materials and details of Mies’s Barcelona Pavilion, Tugendhat house, and in the Krefeld houses, they find a “shameless bankers’ luxuriousness.”27 What in the end, perhaps, the architects realized in their search and curation, and also through their own work, is that there are hidden contingencies yet to be understood by modern architecture. This realization suggests that architectural representation is not just caught up in a particular building, but is indicative of a movement.

While maintenance may initially appear less fundamental to architecture than geometry or other cultural signifiers, it is inextricably tied to the life of buildings. To establish a discourse on maintenance requires us to rethink its associated terms like cleaning and preservation which, while seemingly banal or misunderstood, have far-reaching implications for the conception, construction, and endurance of buildings and of architecture itself. To use them interchangeably ignores their unique protocols that underscore their social, cultural, environmental, and economic differences. Observations like these aim to affirm the visionary potential of architecture while debunking the imagined reality we attribute to great buildings. An essential aspect of this investigation concerns the labor and efforts necessary to ensure architecture’s enduring image. The photographs in this book span the modern and contemporary periods, yet over this long time frame there has been little change in the thinking about endurance, luxury, and the image of architecture with respect to maintenance.

The series of images and short texts included in this book attempt to unpack the history of maintenance in order to understand and uncover its underlying motivations and narratives, as well as alternative models. of architecture. The texts are divided into five parts – “Maintenance and the Urban Image,” “Cleaning and the Politics of Labor,” “Visualizing Decay,” “Modernizing Maintenance,” and “Post-Occupancy and Alternate Architectural Futures” – with specific buildings, art projects, materials, products, and thematic reflections organized to illustrate each part.

These parts are divided not by type but, rather, by important thematics that run throughout the book. “Maintenance and the Urban Image” deals primarily with the iconography of skyscrapers in the context of the city, in order to set the stage for the relationship between image maintenance and building maintenance that is present throughout. “Cleaning and the Politics of Labor” investigates the differences between public and private maintenance through the lens of those respective workforces. “Visualizing Decay” is the one section exclusively devoted to art practices, illustrating the range of ways artists make issues of maintenance visible. “Modernizing Maintenance” deals with the influx of technology and devices developed to reduce labor, while “Post-Occupancy and Alternate Architectural Futures” looks to a variety of contemporary architectural projects and preservation techniques that deal with the afterlife of buildings in interesting and creative ways. Each part begins with a short paragraph and a project that seems emblematic of the section as a whole. The subsequent short texts address more specific concerns. The result is a collection of small fragments strung together in a larger narrative about how to draw attention to the relationship between architecture and maintenance through an investigation of allied fields.

This book was written as a reflection on the contemporary intersections between architecture, art, and culture. We have just emerged from a period of extensive construction, the building up of cities through important and monumental works of architecture, in some cases undertaken without a totalizing image and in other cases unplanned, even excessive. That is to say: in the rush to build, to make new world(s), there has been little consideration for the unmaking – those things that cause wear and tear on the building, from use to weather, and so on.

In the following instances it seems clear that maintenance has been a subject of some interest, but as time passes it will increasingly become an issue for cities in the future, much as it will be for the individual and for society. Maintenance is much more than a metaphor for rethinking culture and society; it exposes a range of imperfections, from unmaking – the decay of buildings, failing joints or chipped glass – to social inequities and unjust labor practices, and to tangible acts that lead to novel design thinking, formal invention, and unprecedented detailing. Even if they are just fragmentary moments, each of these qualities is integral to the underpinning of architecture. This book should be read as a collection of equal images: every image is of equal value. It offers a sort of archive, a curation, a permeable collection that recasts one story about architecture. It is not final; it can be added to or expanded. It is my hope that for someone who reads this book and looks at its images, it will be impossible ever to think about maintenance with indifference, but imperative to recognize that architecture is constructed of several facets, including social facets, one of which is maintenance; and that maintenance can affect design and the creative process.

Notes

1 Interview with Donald Wall (1975), Canadian Centre for Architecture Archives.

2 Hilary Sample, “Maintenance Architecture,” Praxis 6 (2004): 114–121.

3 Ibid.

4 Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998), 2nd edn.

5 Pier Vittorio Aureli, conference introduction, “Architecture and Labor,” a symposium organized by Aureli and the PhD program “City/Architecture,” Architectural Association, London, November 13, 2015, <http://www.aaschool. ac.uk/VIDEO/lecture.php?ID=3256> (accessed March 1, 2015); Arendt, The Human Condition.

6 Martin Heidegger, “The Question Concerning Technology,” in Basic Writings, ed. David Farrell Krell (San Francisco: Harper, 1993), 141.

7 Alison Smithson and Peter Smithson, “Prelude” to The Heroic Period of Modern Architecture (New York: Rizzoli, 1981), 5. The Smithsons wrote the “Prelude” in 1965, but their book was not published until 1981.

8 Heidegger, “The Question Concerning Technology,” 147.

9 Ibid., 146.

10 Ibid., 147.

11 Ibid., 311.

12 David Gissen, Manhattan Atmospheres: Architecture, the Interior Environment, and Urban Crisis (Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press, 2014), 18–19.

13 Nelson Goodman, Ways of Worldmaking (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing, 1978), 70.

14 Rem Koolhaas, “Cronocaos,” Log 21 (Winter 2011): 119.

15 Esther da Costa Meyer, review of Cronocaos, Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 71, no. 2 (June 2012), 248–49. Meyer notes that “Cronocaos also perpetuates stereotypes concerning gender.”

16 See Rem Koolhaas with Jorge Pailos-Otero, Preservation Is Overtaking Us (New York: GSAPP Books, 2014).

17 Rem Koolhaas, “Preface,” in AMO/Rem Koolhaas, eds., Domus d’Autore, Post Occupancy (Domus, 2006).

18 Karsten Harries, The Ethical Function of Architecture (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1998), 255.

19 Alice T. Friedman, Women and the Making of the Modern House: A Social and Architectural History (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006), 132–133.

20 Jacques Derrida, Archive Fever, trans. Eric Prenowitz (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995), 78.

21 Ibid.

22 Harries, The Ethical Function of Architecture, 264.

23 Ibid., 261.

24 Ibid., 256.

25 Ibid.,119.

26 Smithson and Smithson, The Heroic Period of Modern Architecture, 5.

27 Ibid.